Technology Integration

This section provides some background on how technology has been introduced into teaching and learning in K-12 education, and some of the benefits and pitfalls that have been learned by educators during the process.

Early integration of technology into the curriculum yielded some successes and failures that in hindsight might seem obvious, but at the time were learning opportunities for pioneering educators. Technology integration began with the view of using technology as an instructional tool for delivering subject matter already in place in the curriculum (Woodbridge, 2004). It included early attempts to use computers in classrooms and school labs in general content areas with a goal of assisting students in learning how to apply computer skills in meaningful ways (Dockstader, 1999). What educators quickly learned is that many students in middle and senior grades were well ahead of them in knowledge and application, and were exploring the Internet and gaining new knowledge in ways that were unfamiliar. It was unclear for many educators as to what activities would add value, but some early adopters and insightful educators quickly begin piecing together clues from what students were already doing.

It is pointless to integrate (computers and online links) if they don’t add value to the curriculum.”

Paige, 2002

Effective technology integration means using technology effectively in the general content areas to allow students to explore, experiment, and develop new knowledge. It must be done in a manner that enhances learning.

Using software designed for and supported by the business world offered the first opportunities for real-world applications that allowed students to use technology flexibly, purposefully, and creatively. The curriculum must be adapted to drive the use of technology, rather than having technology drive the curriculum. To do this, educators must organize the goals of the curriculum and technology use into a coordinated and harmonious whole. Teachers must understand how best to increase student learning by taking advantage of the ever-developing opportunities provided by the use of technology.

Integrating technology is not about technology—it is primarily about content and effective instructional practices. Technology involves the tools with which we deliver content and implement practices in better ways. Its focus must be on curriculum and learning. Integration is defined not by the amount or type of technology used, but by how and why it is used.”

Earle, 2002

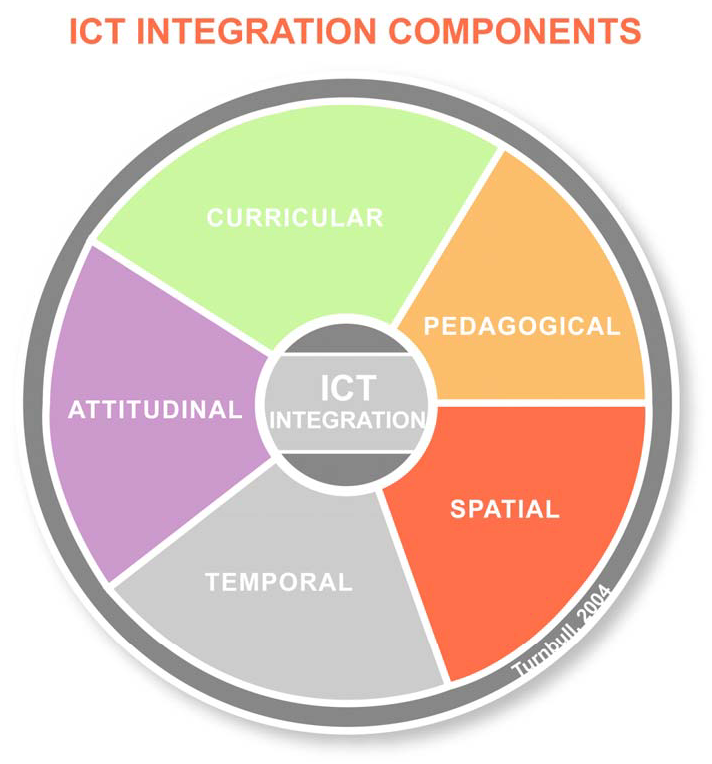

Five Dimensions of Integration

That early realization is just as true today. Effective integration occurs when teachers are actively involved in the plan to make it happen. Part of that plan for development focuses on strategies to educate teachers in a full range of technology uses and in the determination of their appropriate application. In effective technology integration, teachers and students are empowered and supported in carrying out those choices, and parents are invited into the process at the appropriate stage of digital teaching and learning. To be successful in improving student learning opportunities, ICT integration must be viewed in five specific dimensions, or components.

Attitudinal Integration

Early in the process of developing effective strategies for digital teaching and learning, educators identified attitude as an important factor in the successful adoption of the use of technology. This led to the concept of ‘attitudinal integration’.

Attitudinal integration is defined as the ability and extent to which teachers and students take for granted the daily routine use of any given ICT tool or strategy in support of learning tasks or technical operations. Teachers demonstrate the ability to choose ICT tools and strategies appropriate to their activity and need. Promising and successful practices are often shared between colleagues. The use of ICT is not viewed as an ‘add on’. ICT is routinely used with many activities on varying curricular goals and topics. Generally, it is the skill and attitude of the teacher that determines the effectiveness of technology integration into the curriculum (Bitner and Bitner, 2002).

It became clear that an unwillingness to adapt to change and a lack of basic skills and understanding related to ICT integration were and still are serious obstacles to overcome for some teachers.

Curricular Integration

Curricular integration is the ability to which teacher or student use of any given ICT relates to appropriate curriculum goals. ICT curricular integration encourages the development of skills which lead to an understanding of curriculum content.

With curricular integration, concerted efforts are made to analyze curricular expectations and to identify ICT tools or strategies appropriate to achieving defined goals and objectives. Usually, there is some form of assessment in place to monitor the alignment of ICT uses with curricular goals.

One of the obstacles to effective curricular integration can be current assessment practices. With a focus on standardized test results, these may not adequately reflect what students are learning with the use of ICT tools and strategies.

Pedagogical Integration

Pedagogical integration is the extent to which the choice of ICT tools or strategies and the manner in which these are used in the classroom is consistent with sound pedagogical philosophies. Pedagogical integration also takes into account the orientations and intentions of the teacher and the learning styles, abilities, and motivations of the students. Examples of successful integration usually demonstrate a constructivist approach to education (Marshall, 1993). Constructivist teachers are facilitators in their classrooms where students are actively engaged in exploration, invention, and discovery.

Barriers may exist due to a lack of leadership and vision. Using ICT as an instrument for classroom management, allowing students to use computers as a reward or for drill and practice activities hinders integration (Pepi & Scheurman, 1996). Until concepts of learning are modified, technologies will continue to be delivery vehicles rather than tools to support thinking and the development of conceptual understanding (Jonassen, 1995). Using technologies to sustain existing patterns of teaching, rather than to innovate, will continue to create roadblocks (Conlon and Simpson, 2003). An overall general lack of scientifically-based research demonstrating the effectiveness of ICT tools and strategies has created difficulties in adoption and integration of ICT in the classroom.

Spatial Integration

Spatial integration is the extent to which teachers and students engage in ICT-related activities in the same location as other learning activities in a unit. Spatial integration ensures that access and use of a sufficient quantity and quality of ICT tools and strategies takes place within the normal working environment of the teacher and students.

An obstacle to effective spatial integration can occur when resources are limited, requiring ICT use to become an occasional event during which students travel from their normal classroom environment to a computer lab (assuming availability) to work on a particular classroom curricular assignment. For some schools this may be the only option and it can still provide significant benefits. Generally, it is just not as effective as working within the normal learning environment.

Within the spatial environment, other roadblocks can include escalating costs for upgrading existing technology, a lack of adequate technical support, and the supply of adequate and reliable bandwidth from the learning facility to the Internet.

A review of the literature reveals that the existence of adequate and varied support systems within the normal teaching and learning environment is critical with respect to integration (Bitner and Bitner, 2002; Guha, 2003; Hruskocy, Cennamo, Ertmer, and Johnson, 2000; Schmid, Fesmire, and Lisner, 2001; Mouza, 2002).

Temporal Integration

Temporal integration is the extent to which teachers and students engage in ICT-related activities in concert with other prior, concurrent, or subsequent learning activities as part of the curriculum.

When students are on a rotational schedule to access limited or scarce ICT tools (whether in a lab configuration or individual workstations in a classroom), opportunities for collaboration with others are minimized. Spontaneous access to ICT based on identified needs, cannot happen.

Class load and teacher time-management skills can be major impediments to ICT integration (Guha, 2003), as can a lack of sufficient time for teachers to learn newer technologies (Vannatta, 2000). Time constraints also impact access to professional development and training activities, ability to collaborate with colleagues and other professionals, and the ability to simply ‘play’ and experiment. Florida State addresses some of these time management issues by discussing the formation of school management teams (Schmid, Fesmire, & Lisner, 2001). Another approach designed to lessen time management barriers is to create an onsite support system of staff, volunteers, or students (Hruskocy, Cemmano, Ertmer, & Johnson, 2000). Time and again, students have proven to be most effective in supporting the integration and use of technology for teaching and learning.

Each of these five dimensions has implications for how you use, or develop your own digital learning content. The following assignment is designed to make meaning of these dimensions in how you approach and deliver digital learning.

Assignment:

![]() Click on the resource link to download and complete the Dimensions of Digital Learning worksheet.

Click on the resource link to download and complete the Dimensions of Digital Learning worksheet.

Create your own version of the worksheet in MS Word format (.doc or .docx) and complete the chart, responding to the questions that follow. Use the tool provided below to upload a copy of your completed work.